Warrior’s Tale: Hector Hyppolite

Hector Hyppolite: The Godfather of Haitian Art and the Painted Spirits of Truth

Greetings Warriors!

When you speak of Haitian art, you must speak of Hector Hyppolite—not just as a name, but as a movement, a mythology, and a memory that refuses to fade. Born in 1894 in Saint-Marc, Haiti, Hyppolite wasn’t merely an artist—he was a Vodou priest, a visionary, a warrior with a paintbrush, and a soul in conversation with the divine.

He never had formal training. Never studied at a European academy. Yet his works hang in major museums and inspired legends like André Breton, who declared him one of surrealism’s rawest flames. But was Hyppolite really a surrealist? Or was he something deeper?

This is the story of a man who painted spirits, who turned wooden doors into portals, and whose legacy now beats at the heart of Haitian cultural identity.

Hector Hyppolite , Damballah La Flambeau

BUY MY ART🖤

From Saint-Marc to the Spirit World

Born into a working-class family in the coastal town of Saint-Marc, Hector Hyppolite’s early years were marked not by academic art, but by spiritual awakening. His lineage traced back to generations of Vodou practitioners, and by his youth, he had taken on the mantle of houngan—a priest who communes with the spirits.

But Hyppolite was more than a servant of the gods. He was a seer with vision, and he began painting what he saw: the Loa, or spirits of Vodou, not as abstract fantasies, but as living presences—guides, protectors, punishers, and prophets.

These were not surreal dreams. These were his reality.

As a young man, he worked as a shoemaker, carpenter, and house painter, often decorating homes and churches in vibrant colors. During this time, he began painting his earliest spiritual images directly onto doors, walls, and discarded materials—any surface he could find. To him, the world was a canvas.

Hector Hyppolite

No Brushes, No Canvas, No Problem

When the world wouldn't give him the tools, he made his own.

Often too poor to afford proper materials, Hyppolite turned to what he had. He painted with chicken feathers. He used his hands, fingers, scraps of wood, and leftover house paint. The result? Masterpieces that pulsed with life, color, and divine rhythm.

To the elite art world, this was primitive. To Hyppolite, it was truth.

He transformed broken doors and discarded boards into sacred altars. With no brushes, he summoned visions from another world. With no training, he opened the eyes of thousands. He didn’t wait for permission—he created because he had no choice.

Centre d’Art: Where History Met Destiny

In 1944, fate intervened.

The newly founded Centre d’Art in Port-au-Prince, spearheaded by American artist and educator DeWitt Peters, discovered Hyppolite and welcomed him into its growing circle of Haitian artists. He was nearly 50. No formal training. No gallery representation. Just raw, prophetic brilliance.

Within a year, Hyppolite had become the crown jewel of the Centre d’Art, producing over 250 works in less than four years. His bold brushwork, spiritual storytelling, and unapologetically Haitian subjects electrified the art world.

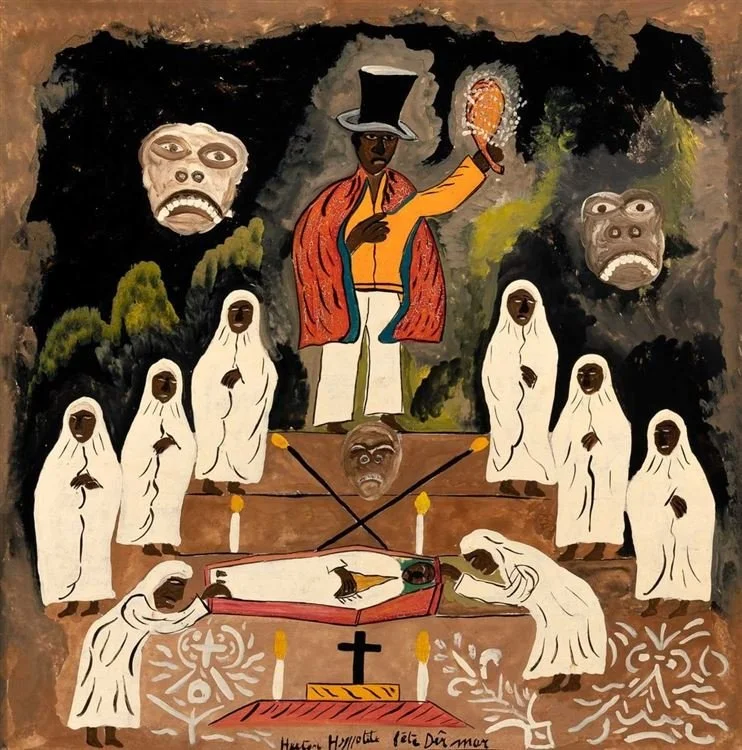

He painted the Loa with wide eyes, elongated bodies, twisted limbs—not out of style, but out of spiritual necessity. His scenes of rituals, divine possession, and ancestral power weren’t symbolic—they were memoirs of the spirit world.

Hector Hyppolite

A Surrealist? Or a Realist of Another Realm?

André Breton, the father of Surrealism, and Cuban painter Wifredo Lam visited Haiti in the mid-1940s and encountered Hyppolite’s work. They were stunned.

Breton called him a surrealist genius, placing him alongside European giants. But here’s the catch: Hyppolite didn’t consider himself surreal at all. What Breton called fantasy, Hyppolite called life.

He wasn’t distorting reality—he was showing us a reality that most of the West refused to see. In this sense, Hyppolite was less a surrealist and more of a hyper-realist of the Haitian spiritual dimension. His works weren’t imagined—they were remembered.

To see a Hyppolite painting is to step into a sacred ceremony, to feel the drums, smell the smoke, and face the gaze of spirits who do not flinch.

BUY MY ART🖤

Hector Hyppolite

The Brush of the Spirits: His Style and Symbolism

Hyppolite’s style is unmistakable. Vivid. Confident. Otherworldly.

He used house paints, enamel, and whatever materials were available, creating with urgency, as if the spirits were guiding his hand faster than the world could understand him. His compositions were often dense and layered, yet balanced—like a ritual in motion.

From Erzulie (the spirit of love and beauty) to Baron Samedi (the gatekeeper of death), his paintings presented the Loa with honor and complexity. No exoticism. No caricature. Only reverence.

He also painted scenes of everyday Haitian life, often with the Loa walking among the living—reminding viewers that in Haiti, the line between this world and the next is not a line at all.

Hector Hyppolite

The Godfather of Haitian Art

To call Hyppolite anything less than the Godfather of Haitian art is to rob him of his crown. He didn’t just make art—he defined it for a nation.

His rise gave credibility to naïve art, a term often used (sometimes unfairly) to describe untrained artists. But Hyppolite wasn’t “naïve.” He was ancient. His knowledge came not from books, but from ritual, experience, and ancestral memory.

He opened the door for generations of Haitian artists who saw in him a blueprint—proof that their voice mattered, that Haiti’s soul was worth painting, preserving, and proclaiming.

And even in death, his voice grows louder.

Hector Hyppolite

Death, Rediscovery, and Art Rescue

Hector Hyppolite passed away in 1948, just four years after his first major public exhibition. He died in poverty, having sold many of his works for meager sums. Fame, as it so often does, came too late.

But his art lived on—and just recently, it was nearly lost forever.

In 2024, as gang violence ravaged Port-au-Prince, rumors spread that Haiti’s beloved Centre d’Art—the very place that once lifted Hyppolite to glory—was next to be destroyed. But in an act of defiance, Haitian police and museum staff launched a two-day mission under heavy gunfire to rescue over 6,000 artworks, including priceless pieces by Hyppolite himself.

It was a cultural war—and Haiti won.

You can read the full story here:

👉 Art vs. Anarchy: Haitian Warriors Save a Nation’s Soul

His work was carried to safety like sacred scripture. Because it is. In that moment, the legacy of Hector Hyppolite didn’t just survive—it became immortal.

Hector Hyppolite

Eternal Influence: A Warrior of the Spirit

Today, Hector Hyppolite is celebrated in major collections around the world—from the Museum of Modern Art in New York to galleries in Paris and beyond. His name is invoked whenever we talk about Haitian art, Afro-Caribbean identity, or spiritual aesthetics.

Yet his work still defies definition. Was he a surrealist? A realist? A prophet? The truth is—he was all of them and none.

He was a warrior with no sword but a brush, no battlefield but the canvas. He stood for Haiti when Haiti was silenced. And now, in a world that’s finally learning to see with spirit, Hyppolite’s vision rings truer than ever.

He didn’t just paint Haitian Vodou. He painted Haiti.

And for that, we honor him—not just as a legend of the past, but as a living flame lighting the way for every Haitian artist still fighting to be seen, still daring to tell their truth.

Renaissance Man - Inspired by Leonardo Da Vinci

Drop a comment below:

And if this article hit you right in the soul, do what warriors do—share it, retweet it, spread it. Let’s keep art, passion, and legacy alive.

Stay bold. Stay curious. Stay creating.

theromuluskingdom.com